3. Domain-Driven Design – Domain Model

The domain model uses the Ubiquitous Language to provide a rich, visual view of the domain. It primarily consists of entities and their relationships. Let's take a closer look.

Entities

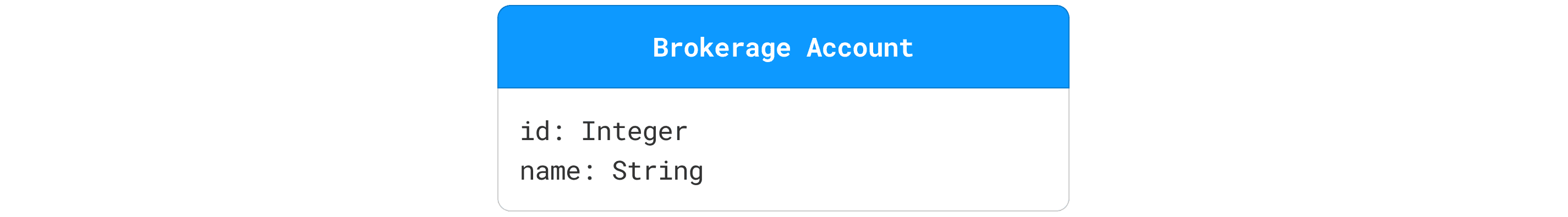

We characterize a domain concept as an Entity when we care about it's

individuality, i.e., when it is important to distinguish it from all other

entities in the system. An important aspect of an entity is that it will always

have a unique identifier. For example, a Brokerage Account has a unique

identifier called id which is an integer. An account with an id of 1234 is

distinct from any other account in the system.

The unique identifier does not have to be a number. It can be any type as long

as it is unique for that entity. For example, the unique identifier for a

Security is its symbol, such as AAPL, which is a string.

Aside from the unique identifier, an entity may have other attributes that define its characteristics, but those attributes do not have to be unique. For example, two brokerage accounts can have the same name, such as "My Brokerage Account", and that's just fine.

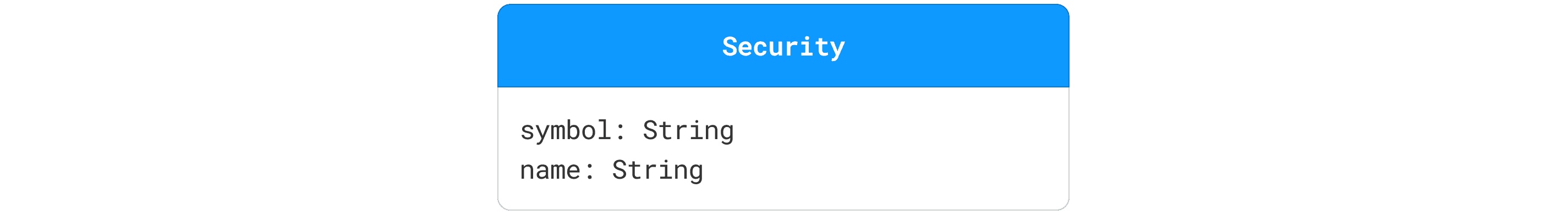

Relationships

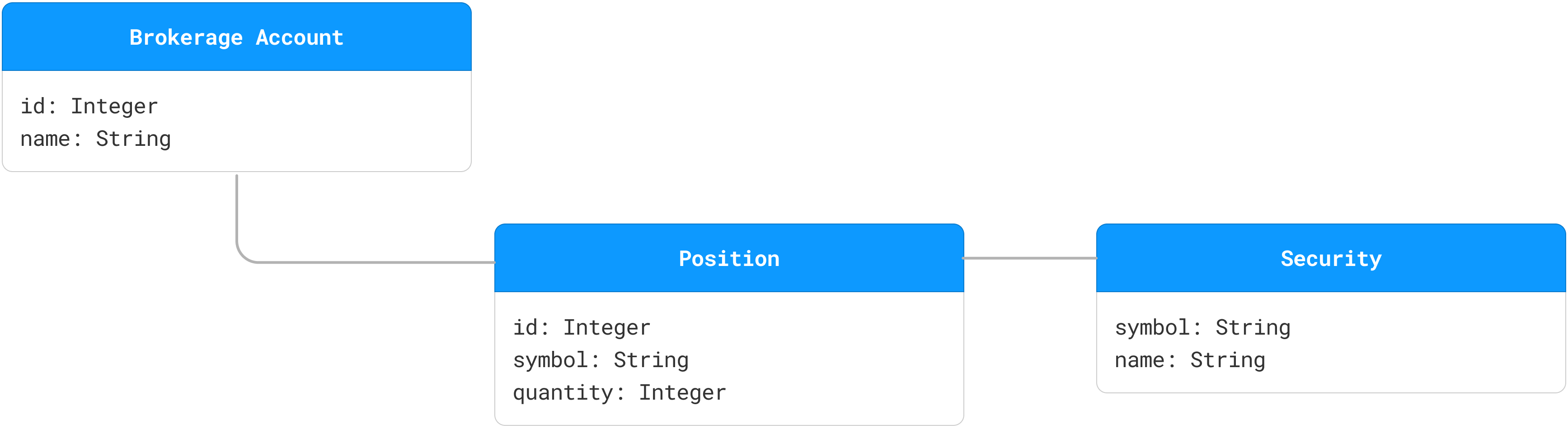

Entities can be related to one another. It's valuable to show such relationships in our domain model. While it's easy to get bogged down with different kinds of relationships, I suggest that you start with the simple Association relationship - all it says is that two entities are related in some way. An association is shown by drawing a line between the related entities. For example, the diagram below shows that a Brokerage Account is related to a Position and a Position is related to a Security.

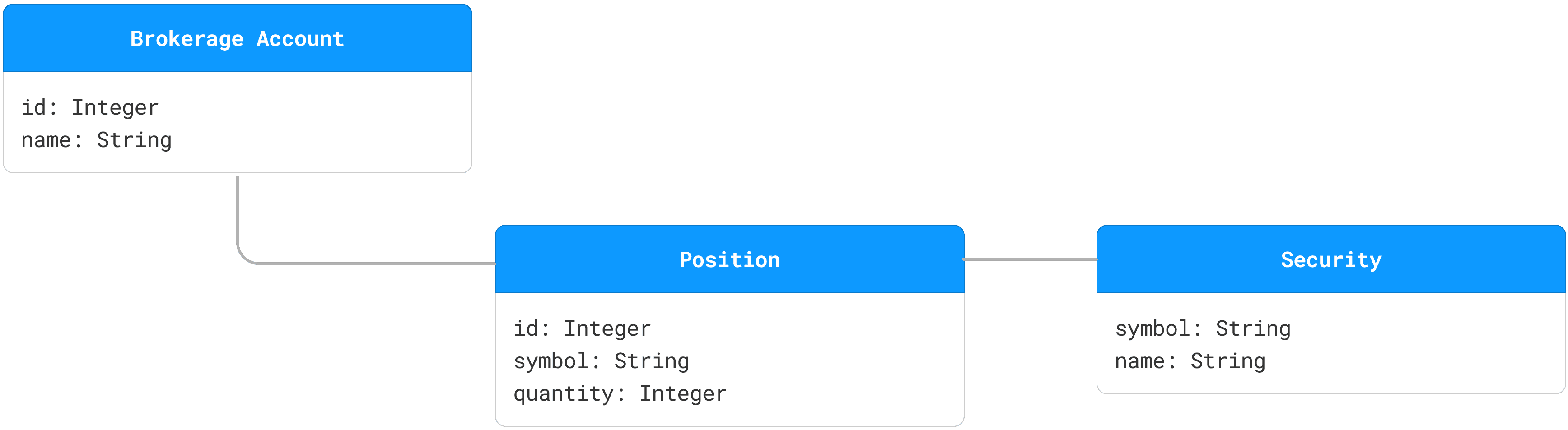

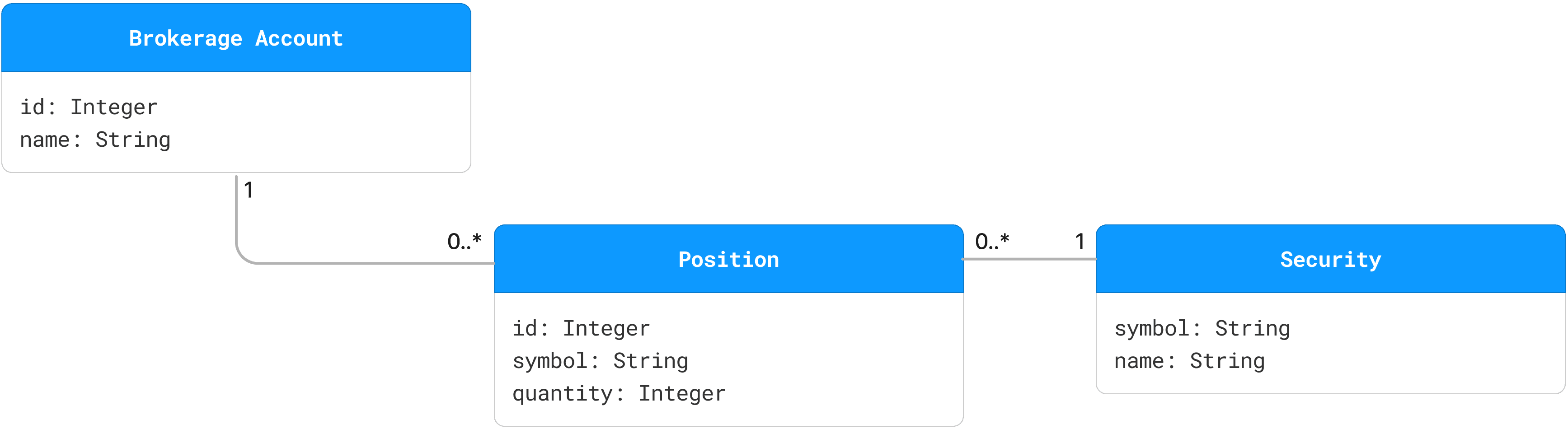

An important aspect of a relationship is the multiplicity of each end. We want

to say that a brokerage account can have multiple positions, but a position is

always associated with one account. This is done by putting a 1 on the

Brokerage Account end and a 0..* (zero-to-many) on the Position end.

Tip: To read multiplicities correctly, read the entity name at one end, then the multiplicity at the opposite end, and finally the entity name at the opposite end.

Using this tip, we can interpret the domain model above as follows:

- A Brokerage Account is associated with zero-to-many Positions.

- A Position is associated with exactly 1 Brokerage Account.

- A Position is associated with exactly one Security.

- A Security is associated with zero-to-many Positions (in different accounts).

If the multiplicity on either end of a relationship is not specified, it should be interpreted as unknown. There is no default value for multiplicity. However, people sometimes leave out multiplicities on either or both ends of a relationship just to unclutter domain diagrams. In fact, many diagraming tools allow suppressing multiplicities for the same reason, even if they are specified.

Note that we have laid out the Position entity below and to the right of the Brokerage Account. This has no "official" meaning in domain modeling, but this vertical orientation helps to suggest a parent-child relationship. A good layout can aid in understanding the domain. I recommend that you pay extra attention to it. A bad layout can cause unnecessary confusion. For example, putting Position above Brokerage Account would reduce the clarity of the diagram. When two entities are peers, you may want to show them side-by-side.

While the diagram above shows one-to-many relationships, you can also have one-to-one and many-to-many relationships. For example, Country to Capital is a one-to-one relationship, whereas Student to Course is a many-to-many relationship.

Value Objects

After entities and relationships, the next important concept in domain modeling is that of a Value Object. A Value Object is a grouping of attributes similar to entities, however the major difference is that value objects have no identity. Let's try to understand this concept using an example.

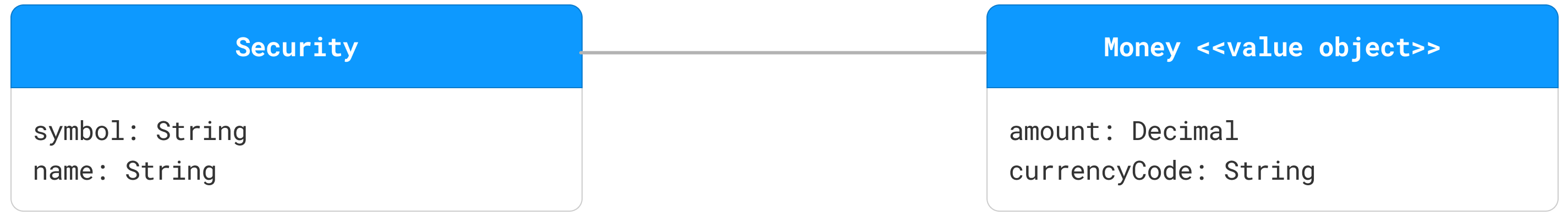

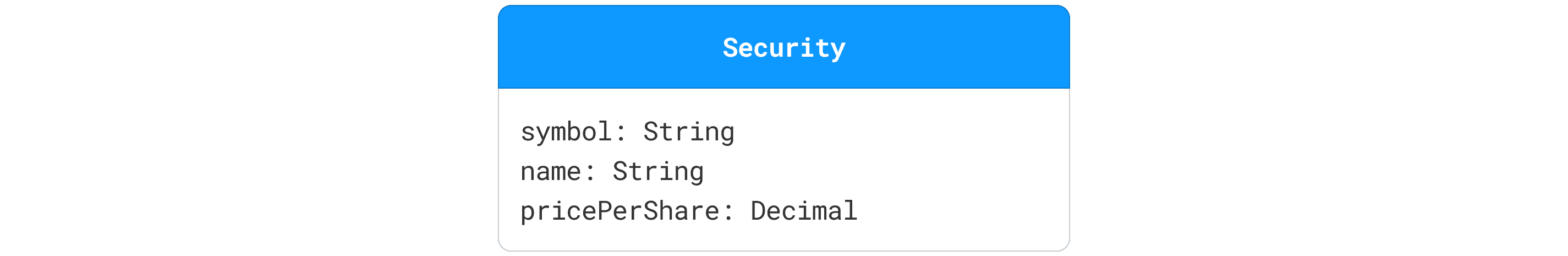

Add an attribute called pricePerShare to our Security entity. An example

of such a security is AAPL with a price of $191.94 per share.

Note that pricePerShare has no units in the diagram above. This may be okay if

our system tracks securities traded only in one country, and hence in one

currency. However, this would not be sufficient for a system that tracks

securities traded in multiple currencies. This situation requires specifying the

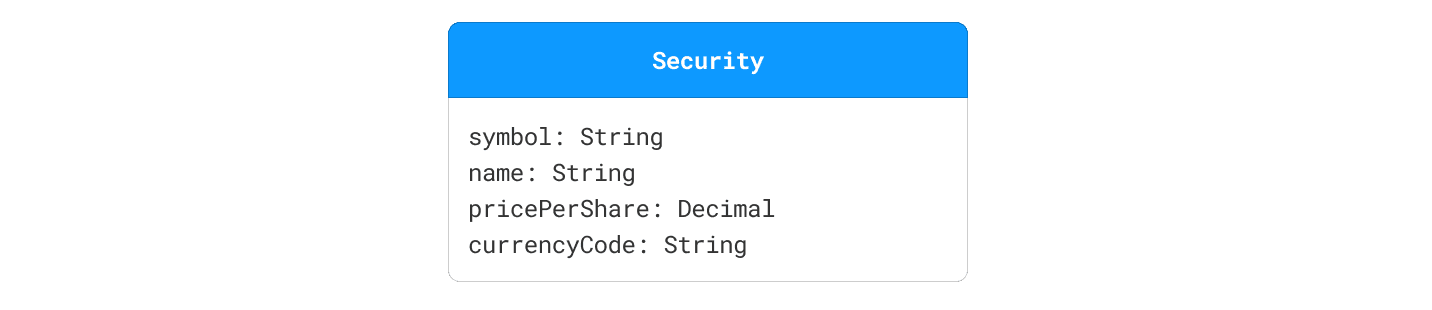

currency along with the numeric price. Let's add another attribute to the

Security entity called currencyCode, which will store values like USD,

GBP, etc.

However, since price and currency code are so tightly related, let's group them

into a separate value object called Money, denoted by <<value object>>.

Note that Money has no identity. While it has multiple attributes, none of

them is a unique identifier. Money is just a value ($100 is $100) – it has no

identity (at least in our domain).

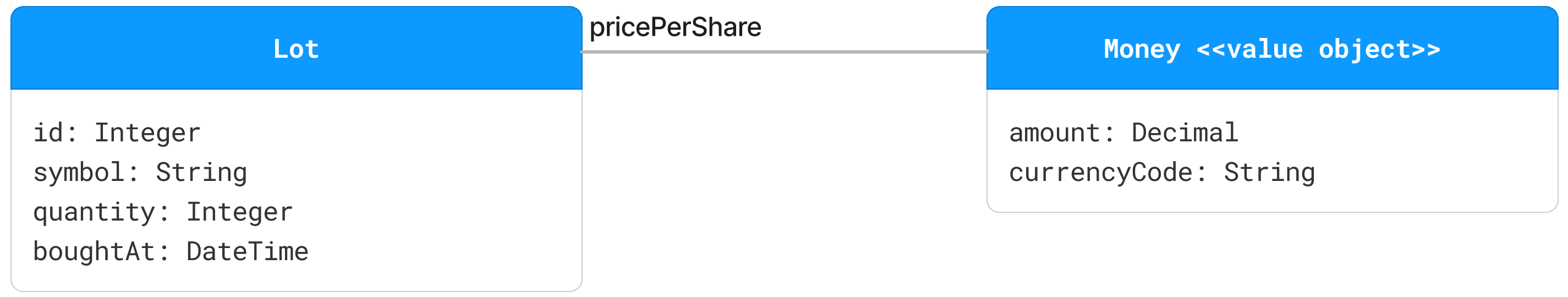

An alternate way to show the diagram above is to replace the pricePerShare

attribute with a relationship between Security and Money called

pricePerShare.

Note: While it shows up in the same place as multiplicity would,

pricePerShareis a role. This should be read as: a security has an attribute calledpricePerShareof typeMoney.

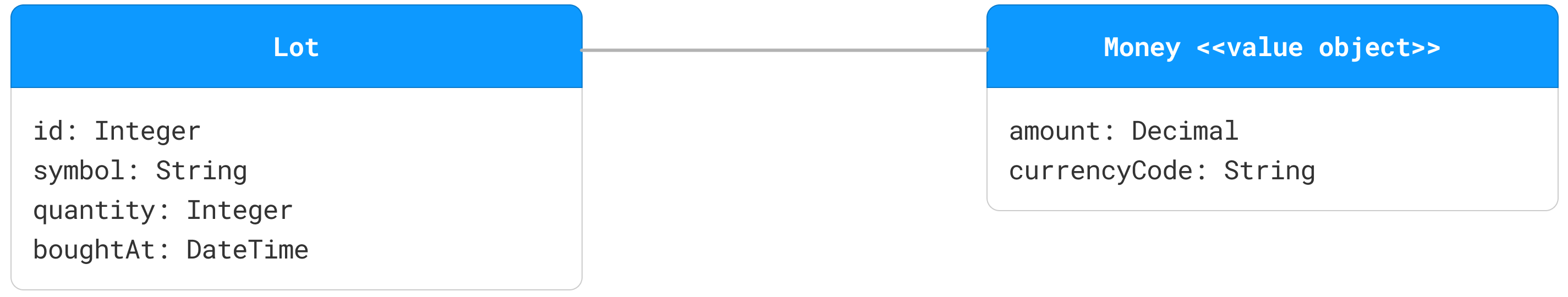

Now that we have Money factored out as a standalone concept, it can be reused

in other contexts where an amount and currency are needed. For example, the

Lot entity described in the previous section can now be modeled as follows:

Entities vs. Value Objects

How can you tell if a domain concept is an entity or a value object? In addition to having a unique identity, an entity encapsulates state that can change. Changes may be so extensive that the object might seem very different from what it once was. Yet, it is the same object with the same identity.

On the other hand, a value object is just a value - it quantifies or describes a property of another object, usually an entity. If the property changes, the value object can be completely replaced by another with the new value. For example, if the current balance of a Brokerage Account changes from $1000 to $2000, you can throw away the Money object that represented $1000 and replace it with a new one representing $2000. Said in another way, Money is fungible.

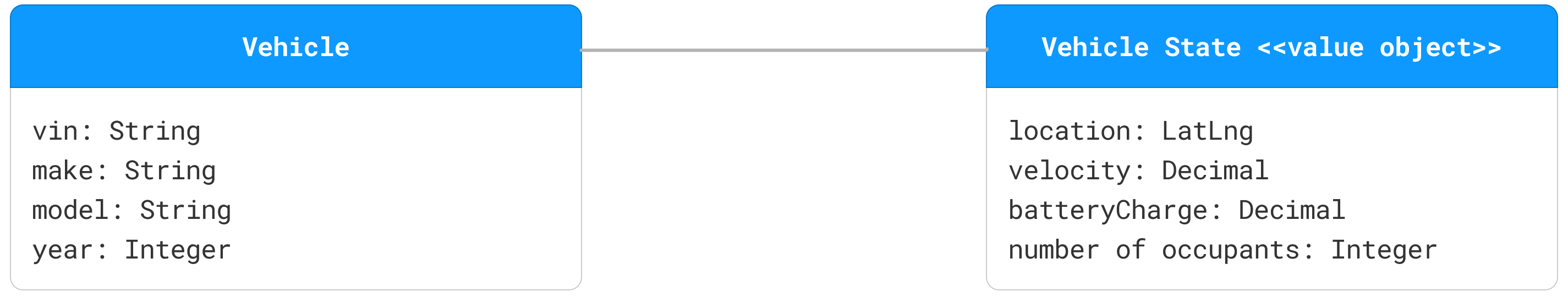

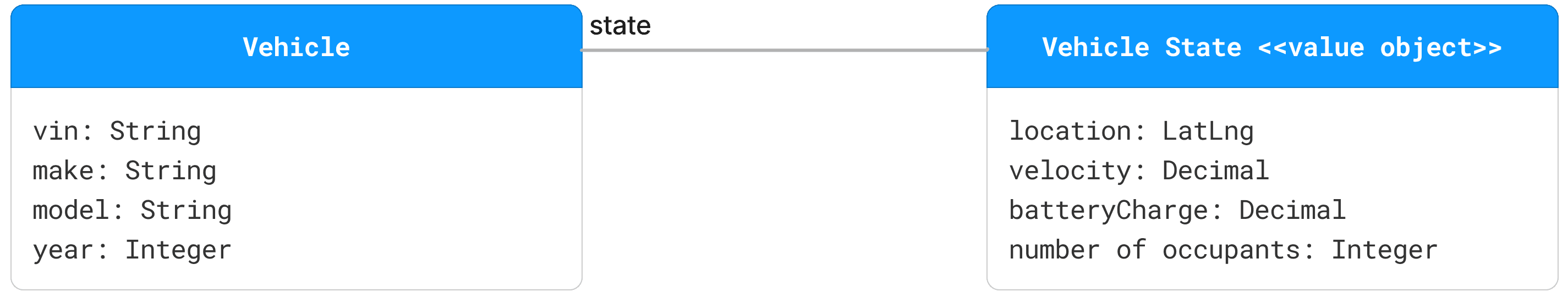

Often, domain model designers will separate out the state of an entity as a

value object. This allows the main entity to remain relatively stable and the

value object to change as the state changes. For example, a Vehicle entity can

be broken into a Vehicle entity and Vehicle State value object as shown

below:

Developers may tend to model value objects as entities because they may need to store value objects as distinct rows in a database table. While this approach may be required to implement value objects in the relational model, don't let it influence your domain model. If you do, your domain model will not reflect true DDD thinking.

For a detailed discussion of these concepts, read Implementing Domain-Driven Design by Vaughn Vernon.

Tips and Tricks

Now that you understand DDD concepts, here are some tips on creating good domain models:

- Avoid introducing software concepts when creating a domain model. This is not an exercise in software design or database design! The focus should be on understanding the business domain and the functional requirements of the system you're developing. Therefore, the domain model should be created and owned jointly by product managers, designers, engineers, and other disciplines involved in the project.

- The process of creating a domain model is very compatible with iterative practices. You don't have to create the entire domain model before building. It's probably good to start with a general idea of the various subject areas in your domain and then dive deep into specific areas as needed.

- Domain-driven Design (DDD) is also compatible with Behavior-driven Development (BDD). While this article covers ubiquitous language and modeling a domain using entities and relationships, BDD focuses more on the behavior of these entities. Together, they complement each other. The behavior of a system cannot be described clearly without understanding the terminology and structure.

- Do not cram your entire domain model into one diagram. A diagram with hundreds of entities and relationships cannot be understood by normal human beings! Break it up into smaller subject areas. Remember the rule of Seven, Plus or Minus Two – limit the number of entities in your diagrams from 5 to 9!

- Avoid crossing of relationships. If you can't draw your diagram without crossing relationships, it is probably too complex. Break it into smaller pieces.

- Engineers: a good domain model should translate directly into the core domain layer of the system without introducing technical concerns like persistence and I/O. We will talk more about this in later sections.

If you've gotten up to this section as a non-technical reader – fantastic! You have enough knowledge to start using domain modeling to solve complex business problems with your team.

If you're an engineer, continue through the remaining sections to understand how to translate your domain model into a working implementation.

In either case, send me your questions and feedback on Twitter and recommend this article to your friends and colleagues wherever you hang out these days – Twitter, LinkedIn, Threads, Slack, Teams, Discord, etc.

In my opinion, there's nothing more fun than hosting a domain modeling party :)